Therapy uses the body's immune cells to fight cancer

A therapy that 'reprograms' the body's immune cells to fight cancer is showing promise, according to early results from ongoing clinical trials.

In one arm of the study, US researchers say 27 out of 29 patients with advanced blood cancer showed 'sustained remissions'. Following the treatment, there was no sign of disease in the bone marrow.

Lead author Dr Stanley Riddell from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center revealed the preliminary findings at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, which is held in Washington.

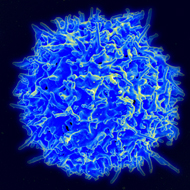

The treatment involves genetically engineering the patient's own T-cells (white blood cells that detect foreign or abnormal cells and begin a process of attack), using synthetic molecules called CARs (chimeric antigen receptors). This enables them to target and destroy cells with a particular target.

Nineteen out of 30 patients with non-Hodgkins lymphoma showed partial or complete responses. In some patients, pounds of cancer were eliminated after a single dose. Dr Riddell says imaging scans demonstrated the disappearance of tumours within weeks of treatment.

Patients involved in the trial had acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Some had not originally been expected to live for more than three months and had previously had relapses or shown resistance to other treatments.

Whilst the findings have prompted a stirring of hope, Dr Riddell stresses that the treatment is "not going to be a save-all" and some patients may still need other treatments, as is the case with chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

The findings have not yet been published in a scientific journal, though a manuscript has now been submitted. Cancer Research UK said the work is "extremely exciting" but it is yet to be scrutinised by experts in the field.

The responses - where patients' symptoms have disappeared - may not mean that the patient has been cured, the charity adds. Without a scientific report, the full details of the trials - including how responses have been measured - are not yet available.

Further research is needed to assess the long-term benefits for these patients, and to better understand the role of immunotherapy in treating cancers. The charity also believes it is of vital importance to adapt the approach for treating 'solid tumours', something it says its own researchers and others are already looking at.

Dr Riddell and the team are still refining their process, which includes reducing the sometimes severe side effects. During the trial, seven patients with high tumour burdens required treatment in the intensive care unit due to a serious 'cytokine release syndrome'. This is being addressed by giving the lowest dose of T-cells to patients with high tumour burdens.

A benefit of their approach, however, is that T-cells can multiply once they are infused in the patient so that, unlike with chemotherapy, the therapy doesn't have to be repeatedly administered. Introducing CARs into two subsets of T-cells also offers more powerful, long-lasting results, according to the team.

They are also working to extend the approach to other common cancers, such as breast and lung cancer. While this presents 'distinct challenges' compared to blood cancers, Dr Riddell says he is optimistic that immunotherapies can be applied more broadly.

Image © NIAID/CC BY 2.0

The BSAVA has opened submissions for the BSAVA Clinical Research Abstracts 2026.

The BSAVA has opened submissions for the BSAVA Clinical Research Abstracts 2026.